Education

Moral relativism: cancer of the West

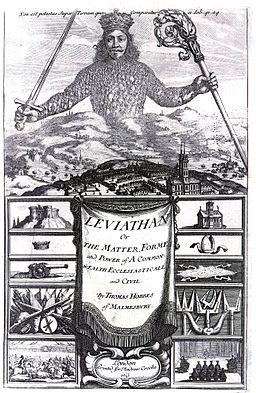

Nothing has had a more pernicious influence in the West than the moral relativism of Thomas Hobbes. His Leviathan is the key source of the most sinister and arguably the most influential work in modern political science. Hobbes taught the Euro-American world that violent death is the greatest evil, which was echoed in the Cold War slogan, “Better red than dead.”

From Leviathan to the moral relativism of today

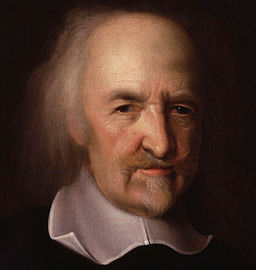

Thomas Hobbes. Portrait (17th century) by John Michael Wright [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

As mathematician James Franklin puts is in his book What Science Knows, the relativist contends that “We cannot know ethical truths (if there are any) except through the urgings of our back-of-brain plumbing, therefore, we cannot know ethical truths at all.” “This,” says Franklin, “is of the same form as “We cannot know mathematical truths except through the calculations of our frontal cortex. Therefore we cannot know mathematical truths at all.”[2] This skepticism issues from the eighteenth-century revolt against the doctrine that moral judgments are wholly, or primarily, or at all, rational.[3]

However, what has most contributed to the ascendancy of moral relativism in modern times is the great success of modern science, especially mathematical physics. Science can boast of universality. The Greek letter = 3.14159265, prominent in Pythagorean geometry, is a universal constant that does not depend on any number system to function and is the only number that defines all circles. The numerical value of (pi) is independent of time and place.

Here is a more revealing example: fire burns in Athens as well as in Zanzibar. In contrast, the moral and cultural values of Athens and of Zanzibar are radically different. Furthermore, unlike the objects of science, which are objective and quantifiable, moral values – say “good” and “evil” – are subjective. They vary from time to time, from place to place, from historical epoch to epoch, from one society or culture to another. On the other hand, 20th century science also speaks of certain mysterious entities called “quarks.” “The theory of quarks,” says astrophysicist Bernard Haisch, “was proposed in 1964. Evidence for the existence of the two quarks that up the proton and the neutron – the up and down quarks – emerged early in the early 1970s”[4] These quarks, which were predicted within the framework of a mathematical theory, have no mass.

This plays havoc with what has long been the reigning theory of knowledge in the social sciences: “empiricism” or “positivism,” which was demolished by, but was oblivious of, the ascendancy of Quantum Mechanics in the 1920s. What a Nobel laureate in physics said of QM can be applied to the “empiricism” or “positivism” reigning in the social sciences:

Our theories, gentlemen, have run amuck.

To 1926 we must return;

Our work since then is only fit to burn.[5]

Although the empiricist dogma, “If you can’t see it, touch it, or measure it, it doesn’t exist,” was refuted by quantum physics, it continued to hold sway in academia, in the social sciences. There it trashed moral values. College students continued to be imbued with the doctrine that our moral values have no objective validity. They are the consequence of our personality and locality. Enter moral and cultural and historical relativism, in short, Nihilism.

Loss of antithesis

Here the question arises: What is obscured and what do we lose as a result of this nihilism? First, and as perceived by Francis A. Schaefer, we lose the ability to think in terms of antithesis:

If a certain thing was true, the opposite was not true. In morals, if a thing was right, the opposite was wrong. This is something that goes as far back as you can go in man’s thinking … As a matter of fact it is the only way man can think…. That is the way God has made us and there is no other way to think. Therefore, the basis of classical logic is that A is not non-A.[6]

The denial of antithesis implies a denial of good and evil. This denial should first be considered in the context of the First World War. In this war civilians and soldiers, the young and the old, experienced the indiscriminate bombings of cities, gas warfare, and horrendous killing fields which left Europe in a deep cultural and spiritual crisis from which it has never fully recovered. This is the back drop of the moral relativism that has emasculated Europe to this day. Moral relativism and cynicism conquered every level of education, first and foremost, Europe‘s colleges and universities, the source of their opinion makers, policy makers, diplomats, and democratic heads of state. The disease crossed the Atlantic and infected higher education in America, where it is firmly entrenched, especially in the social sciences and humanities.

Consider only evil. Back in 1914, at the outset of the First World War, before moral relativism conquered academia, it was stated in the Harvard Classics:

Evil in the broadest sense means disharmony, since any kind of disharmony is source of pain to somebody. But that source of pain which arises between man and nature has in itself no moral qualities. It is an evil to be cold or hungry, to have at tree fall on one, to be devoured by a wild beast, or wasted by microbes. But to evils of this kind, unless they are in some way the fault of other men, we never ascribe any moral significance whatever. It is also an evil for one man to rob another or to cheat him, or in any way to injure him through carelessness or malice; and we do ascribe a moral significance to evils of this kind – to any evil, in fact, which grows out of the relations of man with man. But as already pointed out, the latter form of evil – moral evil – grows out of, or results from, the former, which may be called non-moral evil. Any true account of the origin of moral evil must therefore begin with the disharmony between man and nature.[7]

However, as regards human affairs, we need to bear in mind that it is not unusual for good and evil – or the snow-white and pitch black distinctions portrayed in Arthurian legends – to fall because human nature, even in some of the best and worst cases, is a complex of good and evil, and that sometimes an evil act may result in an unintended good consequence. This is commonsense obscured by moral relativism.

Although Sefer Yetizrah (the Book of Creation) is commonly and simplistically regarded as work of mysticism, its world outlook is very much based on a commonsense. For example:

It is only in a physical being that both good and bad can exist together. Although they are at opposite poles spiritually, they can come together in man. One reason why God created man in a physical world was to allow him to have full freedom of choice, with both good and evil in his makeup. Without a physical world, these two concepts could never exist in the same being.[8]

Now ponder in this connection Deuteronomy 30:19: “…life and death I have placed before you, blessing and curse, therefore, choose life, so that you and your seed will live.” Viewed in this context, evil exists in order that it should be nullified by the good deeds of man.[9] Considered dialectically, evil is enlarges the scope and deepens appreciation of its antithesis or opposite.

More generally speaking, without the idea of antithesis or opposites, there is no coherence or contrast in thought and action, and society collapses into moral anarchy and barbarism. Lost is in the absence of antithesis is any common sense as well as decency.

Coupled to antithesis, common sense turns a welter of mere sensations into a “coherent consciousness of myself as a subject in a world of objects.”[10] Moreover, without antithesis we lose the idea of ordinary decency or confidence in our fellow-citizens intuition of right and wrong, of good and evil. Indeed, without the idea of antithesis we are lost in savagery.[11] “Savage beliefs,” says C. S. Lewis, “exemplify pre-logical thinking …” Savagery therefore magnifies the rule of elemental passions. It renders man beings impervious to civilization. Shakespeare portrays such a creature the te in The Tempest, where Caliban – almost an anagram for “cannibal” – is contrasted with the spiritual Ariel. One conveys the base, the other the refined, inclinations of human nature, as is outlined in Pirke Avot, the Jewish Book of Ethics. Nihilism simply negates this common sense knowledge of human character.

[1] See Theodore Dalrymple, Our Culture, What’s Left of It (Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, 2005), 179, who writes: “It wasn’t until the end of the twentieth century, with its unprecedented prosperity and militant moral relativism, that Tocqueville’s prescience became clear that economic progress was perfectly compatible … with [moral] degradation.” (Plato foresaw this 2,400 years ago, Republic, Book VIII.)

For essays on the moral relativism prevailing in the social sciences, see Paul Eidelberg and Will Morrisey, Our Culture ‘Left’ or ‘Right’: Littérateurs Confront Nihilism (Lewiston NY: Edwin Mellen, 1992). For the prevalence of moral relativism in psychology, see Paul Eidelberg, “The Malaise of Modern Psychology,” Journal of Psychology, Vol. 126, No. 2, March 1993), 109-120.

[2] James Franklin, What Science Knows and How It Knows It (New York: Encounter, 2009), 246.

[3] See C. S. Lewis, 158-159.

[4] Haisch, 83-84.

Ron Chronicle liked this on Facebook.