Tagged

American exceptionalism

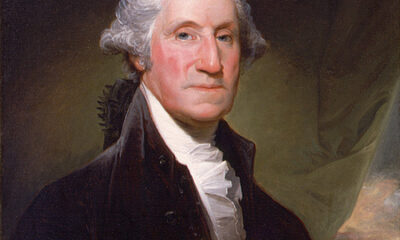

American Exceptionalism begins with the fifty-six extraordinary men who signed the Declaration of Independence.

American exceptionalism begins with exceptional men

To begin to understand this first and most profound foundational document of America, let us first examine the character of its signatories, lest they be confused with the revolutionaries of other countries.

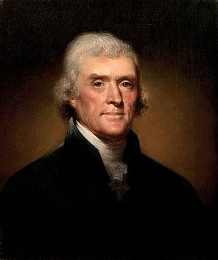

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson, the principal but not sole author of the Declaration, spoke famously of a natural aristoi. On October 28, 1813, in response to a letter from John Adams, Jefferson agreed with his old friend that there is a natural aristocracy among men founded on virtue and talents:

This natural aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature, for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society. And indeed, it would have been inconsistent in creation to have formed men for the social state, and not to have provided virtue and wisdom enough to manage the concerns of society. May we not even say that that form of government is best, which provides the most effectually for a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government?[1]

Alexander Hamilton

One outstanding example of Jefferson’s natural aristoi was his archrival Alexander Hamilton. Born out of wedlock, Hamilton, a man of enormous talent, pride, and ambition, penned these words in Federalist 36: “There are strong minds in every walk of life that will rise superior to the disadvantages of situation, and will command the tribute due to their merit, not only from the classes to which they particularly belong, but from the society in general. The door ought to be equally open to all …”[2]

In his biography of Hamilton, John C. Miller writes:

The period in which Alexander Hamilton lived was an age of great men and great events. In the United States, besides Hamilton himself, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and John Marshall held the center of the stage; while the European scene was dominated by William Pitt, Charles James Fox, and Napoleon Bonaparte. And yet, Talleyrand, whose career is a convincing testimonial of his astuteness in judging men and measures and who was intimately acquainted with the leaders on both sides of the Atlantic, pronounced Alexander Hamilton to be the greatest of these “choice and master spirits of the age.”[3]

It should be noted that Hamilton had four horses shot from under him during the War of Independence and like George Washington, Hamilton was inspired by the creative energy, stamina, and religious sobriety of the American people—qualities that would enable imaginative and resolute statesmen to tap the enormous potentiality of America, a virgin country, and create a Republican Empire of unprecedented scope and character.

Lives, fortunes, and sacred honor

For this architectonic goal, America’s natural aristoi harbored a superb ethics, the Protestantism that unites sturdy individualism and dedication to the common good. Thus motivated, they manfully vowed in the Declaration of Independence, “we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred honor” knowing death would be the cost if captured. Five were indeed captured by the British as traitors, and tortured before they died. Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Nine of the fifty-six fought and died from wounds or hardships in the American War of Independence.

The reputations of these revolutionaries before that war read like a “Who’s Who” in America. No less than forty-two were members of the Continental Congress. Twenty-four were lawyers and jurists. Eight were physicians. Eight were merchants, while nine were farmers and large plantation owners—and all of these gentlemen were well educated. The fathers of some of these aristoi were clergymen and teachers. Like American parents in general, they sought the best education for their sons, many of whom graduated Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia University, etc. It would be a mistake to regard these educated men as “intellectuals,” who in our time tend to be merely bookish and insulated from the rough realities of life. No, they were “personalities,” by which I mean they removed from the multifarious concerns and vicissitudes of life, certain political ideas and moral values and endowed them with urgency and enduring significance.

A sense of history

These aristoi possessed outstanding governing force along with capacious intellects. They knew they were making history not only for themselves but for all mankind. Listen to these words of Hamilton in Federalist 1, which appeared in New York’s Independent Journal on October 27, 1787:

After an unequivocal experience of the inefficacy of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.

We are here given to behold an extraordinary phenomenon: the virtual self-creation of a people! We see this in the Preamble of the Constitution, and we are reminded of the virtual self-creation of the Jewish People when they affirmed the Sinai Covenant.

James Madison

James Madson. Portrait by Chester Harding, 1829-30. Photo coutesy User Daderot on Wikimedia Commons, CCO 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

Having high-lighted Hamilton, a graduate of Columbia, we must introduce his colleague, James Madison, a graduate of Princeton. Madison, the author of the Virginia Plan—the foundation on which the debates at the Federal Convention developed—was one of the two or three most learned members of the Continental Congress; and thanks to his education at Princeton, he was highly skilled in debate.[4] (Students at Princeton studied ten hours a day and held frequent debates in Latin, a vital part of their classical liberal education.) It was said of Madison that he united the talents of the profound politician with those of the scholar. Jefferson, who admired “the rich resources of his [Madison’s] luminous and discriminating mind,” depended on his acumen as a practical politician.[5]

Americans today are the heirs of the noble deeds of these great men. America’s Founding Fathers are rightfully deemed the source of the true meaning of American Exceptionalism.

*Paul Eidelberg, former officer United States Air Force, received his doctoral degree in political science from the University of Chicago. He is the author of more than ten books including “On the Silence of the Declaration of Independence, The Philosophy of the American Constitution, Jewish Statesmanship, and A Jewish Philosophy of History.

Endnotes

[1] H. A. Washington, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (9 vols.; Congressional Edition: New York, 1861), VII, 31.

[2] Hamilton, Madison, Jay, The Federalist (New York; Modern Library, 1937). The term “federalist” is derived from the Latin foedus, meaning “covenant.”

[3] John C. Miller, Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox (New York: Harper, 1959), xi.

[4] Dubbed by his admirers as the “Father of the Constitution,” he demurred: “The Constitution was not, like the fabled goddess of wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands.” Quoted in Politico (Arlington, Va,), March 16, 2011.

[5] Miller, 85.

-

Education3 days ago

Education3 days ago‘Grading for Equity’: Promoting Students by Banning Grades of Zero and Leaving No Class Cut-Ups Behind

-

Civilization5 days ago

Civilization5 days agoEarth Day Should Celebrate U.S. Progress & Innovation

-

Family2 days ago

Family2 days agoIdaho defends against abortion mandate

-

Civilization3 days ago

Civilization3 days agoNewsom plays silly abortion politics

-

Education5 days ago

Education5 days agoThe Intifada Comes to America. Now What?

-

Constitution1 day ago

Constitution1 day agoPresidential immunity question goes to SCOTUS

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoEarth Day – part of cultural Marxism

-

Civilization4 days ago

Civilization4 days agoWaste of the Day: China Still Owes Over $1 Trillion to American Bondholders

Wanda Stewart liked this on Facebook.

Ann Heimstead Lawler liked this on Facebook.

Steven Garrett liked this on Facebook.

Sarah Hutton Messecar liked this on Facebook.

That is good, Terry. President TRUMP showed the same stuff. What a brave, selfless American to seek a position, a pay cut, and pure punishment to help make America great again.