World news

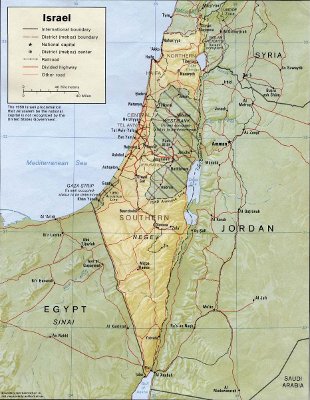

Settlements in Israel: legal or not?

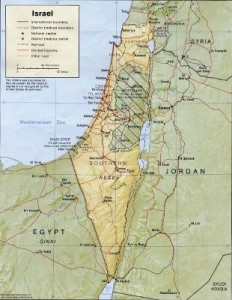

Are settlements in Judea and Samaria (“West Bank”) legal or illegal? What do the Geneva Conventions say? And does it matter, and to whom? As ever, those who press the point most vociferously have forgotten, if they ever knew, the history of the region. And some critics are in fact throwing off on Israel, regarding something they did themselves.

How Jewish settlements began

Michael Curtis, in his new [amazon_link id=”1933267305″ target=”_blank” container=”” container_class=”” ]release[/amazon_link] Should Israel Exist?, points out (page 214) that the modern history of Jewish settlement, side-by-side with Arab enclaves, dates back to the British Mandate under the League of Nations. Article 6 says:

The Administration of Palestine, while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced, shall facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions and shall encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish agency referred to in Article 4, close settlement by Jews on the land, including State lands and waste lands not required for public purposes.

Moreover, ample archaeological evidence shows a Jewish presence in all the lands west of the Jordan River at least since 1406 BC (and more likely 1450 BC). True enough, modern detractors of the Republic of Israel dispute even whether a sovereign Kingdom of Israel or Kingdom of Judah existed between 1095 BC (the coronation of Saul) and 586 BC (when Nebuchadnezzar II sacked Jerusalem). Again, archaeology says otherwise.

The current dispute is about settlements that sprang up after the Six-Day War of June 5-10, 1967. On September 1, 1967, the Arab League resolved to get those lands back, by any means. They used the term occupied lands and never specified which lands they meant. They did speak specifically of driving Israeli forces out of the lands they took since June 5, but did not say where the driving would stop. Moreover they said that Israel had acted aggressively. In fact, the Israelis acted in self-defense. That is something no Arab leader at the time, and few Arab leaders today, care to admit. The main reason: they don’t think that something called “Israel” has a legitimate “self” to “defend.”

In any event, then-Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, taking advice from his friend Yigal Allon, decided to settle Jews on certain strategic regions that would make Israel more defensible in future (like the mountains to the west of the Jordan Valley). He also decided to resettle Jews in the Jewish Quarter of East Jerusalem and in Gush Etzion, Hebron, and other areas that the Jordanians drove the Jews out of in 1950.

And no Arab leader has accepted a Jewish presence in any of those lands. (Though ironically, some Arab residents of East Jerusalem said last fall that they would rather become citizens of Israel than “citizens” of a Palestinian state.)

At least one Israeli official at the time, Theodor Meron, wondered in writing whether settlements would break international law. His letter (in Hebrew) is one of many historical documents that Gershom Gorenberg has put together to support his call for Israel to withdraw completely from “the West Bank” (that is, Judea and Samaria) and leave it to the Arabs. (See also this piece by Gorenberg in The New York Times, saying that Meron and others said that the settlements policy would turn tragic.)

Settlements and international law

The law, or treaty, that relates to settlements is the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. This Convention protects civilians living in a country or territory that an invading force seizes from another. The German armies routinely cleared native people out of their homes and villages, and moved Germans into those areas instead. Some of the people the Germans deported died on the forced march, or died slowly in the unsanitary conditions that the Germans forced them into. The Fourth Geneva Convention condemned all these practices.

The Article of that convention, that Israel’s detractors routinely say forbids the settlements, is Article 49. It reads:

- Individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory to the territory of the Occupying Power or to that of any other country, occupied or not, are prohibited, regardless of their motive.

- Nevertheless, the Occupying Power may undertake total or partial evacuation of a given area if the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand. Such evacuations may not involve the displacement of protected persons outside the bounds of the occupied territory except when for material reasons it is impossible to avoid such displacement. Persons thus evacuated shall be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased.

- The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated.

- The Protecting Power shall be informed of any transfers and evacuations as soon as they have taken place.

- The Occupying Power shall not detain protected persons in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand.

- The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.

This text uses certain technical terms, that show yet again why no one should read one article of a convention, or constitution, in a vacuum.

Protecting Powers

What is a “Protecting Power”? Who appoints a nation-state or non-governmental organization to that role? Article 9 sets forth the duty and authority of a Protecting Power but does not discuss who that Power shall be. Article 11 says that the “High Contracting Parties” may, if they wish, appoint an impartial “international organization” as the Protecting Power. (Article 10 says that the International Red Cross may keep doing what it has always done, but does not make the Red Cross a Protecting Power.)

Is the United Nations, then, the Protecting Power in Judea, Samaria, and the Golan Heights? (The Israelis retro-ceded the Sinai to Egypt in 1979 under the Camp David Accords, and left Gaza to its own devices in 2002.) Because the UN has its Relief Works Agency in place in Judea and Samaria, the UN might call itself a Protecting Power. But is the UN an impartial body? Resolution 3379 (30th session), the “Zionism is racism” resolution, strongly suggests that it is not.

High Contracting Party and Occupation

The Convention does not define “High Contracting Party,” either. Presumably that phrase refers to any country that signed the Convention. Israel did sign in 1951.

More to the point, who decides when a land is occupied? For that matter, who decides where some land leaves off and other land begins? Over centuries of international law, neighboring States decide their boundaries by treaty. The northern border of the mainland United States derives from a series of treaties with the British; the southern border derives from the treaty that ended the Mexican War, plus the Gadsden Purchase Treaty of 1853.

In contrast, the only lines that mark the borders of Gaza, Judea-Samaria, and the Golan Heights, are armistice lines. The 1949 Armistice Agreement says that those lines are not permanent borders. They are strictly matters of convenience. The Camp David Accord set the boundary between Israel and Egypt. The Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty (1994) sets the boundary of Jordan along the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers, through the Dead Sea, then southwest along the Emek Ha’arava (or Wadi Araba in Arabic) line to the Gulf of Aqaba. Moreover, Jordan’s King Hussein gave up any interest in the “West Bank” in 1988, six years before Jordan concluded that treaty.

That Jordan even had Judea and Samaria to begin with, was an act that only one country (Pakistan) recognized as according to international law. That happened in April of 1950. Jordan did not even sign the Fourth Geneva Convention until 1951. (Israel signed in the same year.) The only reason that Jordan could do this was that no sovereign State existed to claim the region. The Palestinians never set up a State in 1949, after the Armistice. They never once talked of statehood until after 1967. (And even then, they consider that their State must include all of Israel proper, not merely the “West Bank” and Gaza.)

The Six-Day War did not begin in a vacuum. A UN force had camped in the Sinai since the 1956 Sinai Campaign. President Jamal abd al-Nasr (Gamal Abdel Nasser) of Egypt told the UN to get its troops out. The Secretary General (U Thant) pulled them out, without even getting Security Council orders so to act. (If that sounds familiar, it should: the man now holding office as President, Barack H. Obama, acted similarly in Libya, without so much as a by-your-leave to Congress.) Al-Nasr then moved troops to the Armistice Line, and then closed the Straits of Tiran. That broke the Geneva Convention of 1958. (Article 16, paragraph 4, deals with “innocent passage” through a narrow strait. See this commentary.)

On June 5, Israel went to war with Egypt, to contest the closure of the Straits, to crush what looked like an invading force before it could move, and to destroy Egypt’s Air Force on the ground. As the bombers of the Israel Air Force returned to base, Jordanian lookouts in the “annexed” West Bank saw them, mistook them for Egyptian bombers, and launched their own attack. That is why the IDF moved beyond the Armistice Line to the Jordan River. (Israel moved into the Golan Heights for a third reason: to stop the repeated terrorist attacks that Palestinian “guerillas” had launched from that quarter, after the Syrians refused to stop them.)

So in what sense does Israel “occupy” any of these lands? Again, Israel has left Gaza to its own devices and given back the Sinai. As part of that, Israel has evacuated hundreds of settlers from those two regions and transferred them back to Israel proper. There is the forced transfer of civilians: transfering its own people out of settlements in disputed territories (in one case, after handing them back to another power) and back home.

Israel itself relies on this argument: terms like “occupation” and “Occupying Power” have no meaning when no High Contracting Party or other State exists or existed having a valid claim to the disputed region or regions. So whatever else anyone says about settlements, they are in disputed, not truly occupied, territory.

Government transfers

To be illegal, settlements must also involve deporting or transferring people out of the home country to settle a disputed area. No one seriously says that the Republic of Israel has deported anyone to Judea or Samaria or the Golan. (That would be the same as an ancient Roman emperor banishing someone to an island 400 Roman miles away from Rome.) So what is a transfer? Answer: the one doing the transferring is the one deciding either where to live or to tell another person where to live. When a person, of his own free will, sells his house (or quits his apartment or other living place that he rents) and moves to another, no government transfers him. If anything, he transfers himself.

All settlers are volunteers. So none of these settlements break the “no-transfer rule,” because no transfer has happened.

Taking of property

The more serious argument is that the Israelis expropriated vast tracts of land to build the settlements. On March 30, 1976, the Palestinians living in Judea-Samaria and Gaza went on a general strike and staged many mass protests. Palestinians have remembered this event ever since; they call the date Land Day.

Article 49 does say that a country occupying the territory of another must not force people off their land in that territory. That rule applies, except when military security demands such action. The Article further says that an occupying army may not drive people out of the territory completely. The IDF has never done this. At most, they have told people that they can live somewhere else in the region.

And, uniquely in the history of belligerent occupation or anything like it, the Israel Supreme Court has extended its jurisdiction to such cases. So any Arab who feels that Israel took his property to build settlements, can have his day in court. Nor does that court always rule in favor of the government. So if the government wants land for settlements, it must show adequately that they must take the land for military or population security.

Hypocrisy

Critics of Jewish settlements are hypocritical in one critical respect: the Jordanians did many things that Israel’s detractors accuse Israel of doing today. They seized Jewish land and property in East Jerusalem, Judea, and Samaria, and drove the Jews out of those lands completely. The only reasons that no one talks of Arab “settlements” in the region are:

- The Jordanians probably did not have to transfer any of their people into the region, or even suggest that they relocate of their own will, and

- Few outside observers have any sympathy for Jews, anyway.

Still, the record is clear. East Jerusalem is a prize example. The Jordanians utterly demolished the Jewish Quarter of the Old City while they controlled it. In 1967, one of the first things the Israeli government sought to do was to rebuild the Jewish Quarter. (Their first internal dispute was with the Antiquities Authority, after engineers discovered ruins beneath the streets of the Jewish Quarter, ruins that no one even knew were there!) Yet the Arabs call the Jewish Quarter one of the “settlements” in the West Bank. They deny that any Jew ever lived there before 1967. Then again, they deny that any Jew lived in the entire region before the British Mandate.

If settlements disappear, what then?

What would the Arabs do if settlements disappeared tomorrow? Would that satisfy them? Never once has anyone claiming to speak for Palestinians acknowledged that Israel exists or should exist. To them, all Israeli cities and villages are “settlements,” wherever they stand. Before anyone asks for justice, he must decide to do justice in return. Vowing to “wipe Israel off the map” or “push them into the sea with the rest of the garbage” is not a plea for justice; it is a declaration of war. Furthermore, Israel has withdrawn settlements from certain territories. The result has been more danger, not less, to the security of Israel proper. The danger from Gaza is obvious. Even giving up the Sinai seemed a good idea then. Today the Muslim Brotherhood will field a candidate for President of Egypt (after they said they wouldn’t), and repeatedly talks of breaking the Camp David Accord. Who, then, could blame any veteran of the Sinai settlements for saying that he and his fellow settlers should have stayed?

In fact, the demand that Israel stop building settlements, and withdraw all settlements now standing, is part of the old demand to withdraw behind the 1949 Armistice Line. That line is indefensible and everyone knows that. So Jewish settlements, wherever they stand, are a side issue to the more basic argument of whether Israel has any right to exist as a country.

Related:

Israel: a new primer

ARVE Error: need id and provider

[amazon_carousel widget_type=”ASINList” width=”500″ height=”250″ title=”” market_place=”US” shuffle_products=”True” show_border=”False” asin=”B002EQA102, 0471679526, 044654146X, 0789209284, 0688123635, 0345461924, 0253349184, 1929354002, B00005S8KR, B000RPCJPC” /]

Terry A. Hurlbut has been a student of politics, philosophy, and science for more than 35 years. He is a graduate of Yale College and has served as a physician-level laboratory administrator in a 250-bed community hospital. He also is a serious student of the Bible, is conversant in its two primary original languages, and has followed the creation-science movement closely since 1993.

-

Executive2 days ago

Executive2 days agoJanuary 6 case comes down to selective prosecution

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoRolling the Dice on Republicans: Has the Right Become Delusional?

-

Civilization21 hours ago

Civilization21 hours agoPresident Biden Must Not Encourage Illegal Mass Migration From Haiti

-

Executive23 hours ago

Executive23 hours agoWhy Fatal Police Shootings Aren’t Declining: Some Uncomfortable Facts

-

Civilization2 days ago

Civilization2 days agoBiology, the Supreme Court, and truth

-

Guest Columns22 hours ago

Guest Columns22 hours agoWhat Was Won in No Labels’ Crusade

-

Entertainment Today24 hours ago

Entertainment Today24 hours agoWaste of the Day: Throwback Thursday: Millions Went To Video Game ‘Research’

-

Constitution22 hours ago

Constitution22 hours agoEquality Under the Law and Conflicts of Interest in New York

[…] Convention does not apply to the West Bank. The reasons seem similar to those that CNAV cited earlier: no Israeli officials forced any Jew to live there. In fact, Jordan annexed the West Bank in 1950 […]

[…] Settlements in Israel: legal or not? […]

[…] resolution says the settlements are “illegal,” but won’t say why. (CNAV has gone over this before. See also this treatment of the Levy Report.) More seriously, the resolution accuses Israel of […]